Spice Modelling And

Distortion Reduction

Analog Tape Recording

Kevin Aylward

kevin@kevinaylward.co.uk

Abstract

To

reduce the distortion of analog magnetic tape records, a larger higher

frequency, oscillator bias is added to the audio signal that is being recorded.

The reason for this is to minimize the distortion that is generated due to the

hysteresis of the magnetic material of the recording tape.

This

article provides a technique for the construction of standard spice models that

are able to model the essential characteristics of systems with this hysteresis.

The technique allows for an approximation of sufficiently accuracy to

illustrate hysteretic generated distortion and how it is reduced by the

addition of high frequency bias.

In

particular, the addition of a high frequency bias signal reduces distortion

because the large positive and negative magnetizations of the core due to the oscillator

bias signal, results in the audio signal magnetization being effectively a

linear average of the oscillator bias signal.

Key

words: high frequency bias, distortion, hysteresis, analog, tape recording,

spice, modelling

A Hysteresis Model

The

essential problem of modelling hysteresis is that it is a static or DC effect that

has memory. That is, the next value depends not only on the present value, but

also on the last value. However, this last value dependence does not depend on

time. This results in a multivalued transfer function. Unfortunately, standard

spice does not directly support this type of modelling. All dependence on the

last value in spice is usually the result of a linear integration, which

inherently results in frequency dependent transfer function and no account of

distortion mechanisms. A way around this

problem is to simply recognize that one can cheat. Analog models only have to do what they need to do, approximately, over a finite range

of frequencies. Analysis shows that a small capacitor in conjunction with nonlinear

diode resistances can be used to continuously store the last value of a signal

before it changes slope direction to provide an effective hysteresis, but

without unduly being dependent on frequency. This is in contrast to some spice “hysteresis”

models that are only two output state models that do not allow for a continuous

transfer function.

The Linear Model

The

following schematic forms the basis of a continuous hysteresis model that may

be used for modeling, for example, magnetic cores:

The

output voltage of this block, essentially, linearly follows the input, but with

an offset voltage. When the input turns around, the capacitor holds the voltage

such that there is a dead band starting from the peak voltage reached. The key

principle of operation is that there is nonlinear impedance that has a sharp

ratio of resistances for forward and reverse bias conditions. The standard

diode equation is the simplest, but not a necessary equation for the technique.

It is used here to illustrate the method. Alternative equations may be used to

fine tune the response characteristics. The input voltage may also be further

processed in order to achieve different nonlinear transfer curves. The example

here uses a behavioral model for the diodes of:

b1 a c

i={is}*(exp({k}*v(a,c)) - 1)

To

achieve an accurate model, the values of the components, are chosen such that

frequency effects are minimized, over the range of frequencies that the system

is desired to be modelled over. The time constant of Rload

and Cmemory should be such that the last voltage

before the turn around does not leak too much. The charging current through the

drive impedance (diodes in this particular case) is such to not limit the

response of the system over the desired operating frequency range.

The

above topology results in the following set of transfer functions, and

hysteresis graphs for various input voltages and frequencies:

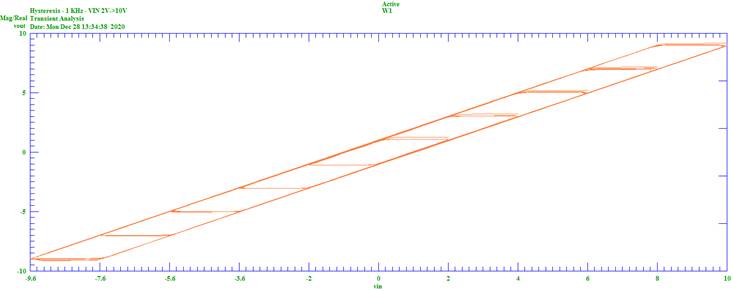

Figure

1 – Ramped Input Transfer Function - F=1KHz,

VIN=2V, 4V, 6V, 8V, 10V

Figure 2 – Ramped Input Transfer Function - F=1MHz, VIN=2V, 4V, 6V, 8V, 10V

Figure 3 – Hysteresis - F=1kHz, VIN=2V, 4V, 6V, 8V, 10V

Figure 4 Hysteresis - F=1MHz, VIN=2V, 4V, 6V, 8V, 10V

The key points of the graphs, are that, over a 1000:1

frequency range, the voltage transfer function and the hysteresis voltage are

relatively constant, thus forming a good approximation to real DC hysteresis.

In general, one constructs a spice behavioural resistance

from a controlled current source that has the required forward and reverse

characteristics. For example, the hysteresis dead band voltage may be adjusted

by changing the diode parameter “N” from its default value of “1”.

Analog Tape

Distortion

The above model can now be used to analysis distortion

reduction in analog tape recorders when a high frequency sinewave bias signal

is added to the analog signal to be recorded.

To first order, consider that the tape does not enter

saturation such that this model does form a reasonable first order model to a

real core. That is, the dead band reflects the remanence of the core and that

this magnetic hysteresis results in a sinewave analog signal being clipped in a

manner to that shown in figures 1 & 2, with hysteresis shown in figures 3

& 4. Thus, it is evident that these hysteresis characteristics, causes

significant distortion.

Consider a large high frequency sinewave magnetization

signal. Even with hysteresis, the average of the recorded signal will be zero.

If this signal is now dc offset with another signal, the HF signals will now,

essentially, swing around this offset signal, independent of the dead band as

the large signal always drives the magnetization through the dead band. This is

true, despite the HF signal having waveform distortion. Thus, the average of

the HF bias signal will equal the offset signal, and it is this average value

that forms the recorded signal for playback. In this way, the offset signal

does not experience the dead band distortion as it would do if it was the only

applied signal. The wave shape of the HF bias does not matter so long as its

frequency is high enough such that all spurious signals are outside the bandwidth

of the desired signal, as they can be filtered out. A schematic illustrating

this is shown:

Figure 5 - Tape Distortion Reduction Schematic

The schematic shows the sum of 3 sinewave voltages.

Two signals represent a multi frequency input, with the other, the HF bias

signal. The two signals illustrate the effect of intermodulation distortion. A

nonlinear system will show sum and difference frequencies.

Typical, raw single input/output signals are shown

here:

Figure 6 - Single Frequency Signal, VIN=1V

Figure 7 - Single Frequency Signal, VIN=12V

Figure 6 & 7 shows the effective magnetization

signal “voltage lagging” it’s input, and subsequently

severely distorted due to the hysteresis that occurs when the signal changes

direction. A standard spice technique that generates a voltage lag would not

model this distortion of the waveform peaks.

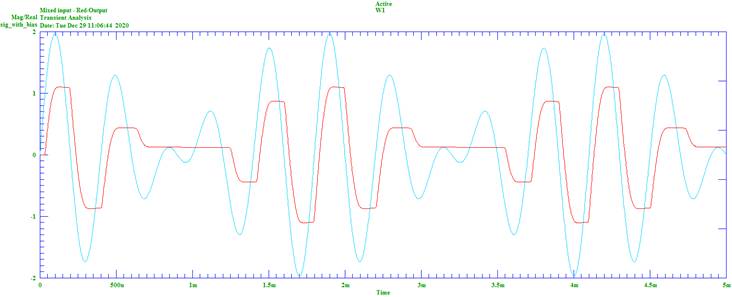

The mixed, raw signal is shown here:

Figure

8 Mixed Frequency Signal, VINA=1V,

VINB=1V

Figure 8 shows that there is significant distortion of

the input signal.

FFTs of the mixed, unbiased signal are shown here:

Figure 9 - Unbiased Mixed Signal FFT VINA=1V, VINB=1V

Figure

10 Unbiased Mixed Signal FFT, VINA=6V, VINB=6V

These shows significant 500 Hz, 1kHz

and 1k5 intermodulation distortion for the unbiased condition

The mixed, HF biased signal is shown here:

Figure 11 - HF Biased, Mixed Signal

The FFT of the mixed, HF biased signal is shown here:

Figure 12 - HF Biased Mixed Signal FFT

The addition of the HF bias thus shows greatly reduced

intermodulation products.

Summary

This article has demonstrated a technique that allows

for the modelling of hysteresis within the capabilities of standard Spice. It

has also been shown how adding a high frequency bias signal to an audio signal

reduces distortion.